廣告 ADS

In a myth spun from the synthetic threads of the global supply chain, ZARA is a multi-headed hydra regurgitated from the dregs of fast fashion spectacle. Between the aporias of seamless production and logistical space she finds new positions from which to contest the neocolonial frontiers of substance and thought.

Available for purchase HERE.

1

ZORBA! A man with such virility as to be unstoppable, his brutishness flying in the face of reason. “Madness!” Amancio Ortega would often exclaim, repeating the culminating line of the film Zorba the Greek to himself like a mantra: “A man just needs a little madness or else he never dares cut the rope and be free.” People often wonder how the world’s most successful fashion retailer rose to such prominence. The path was long and arduous, but comprised less of bricks and cement than of waterways. This tale is about more than just a single man, however. This is a tale about a creature known as the hydrofemme. You may know her best by the name of ZARA.

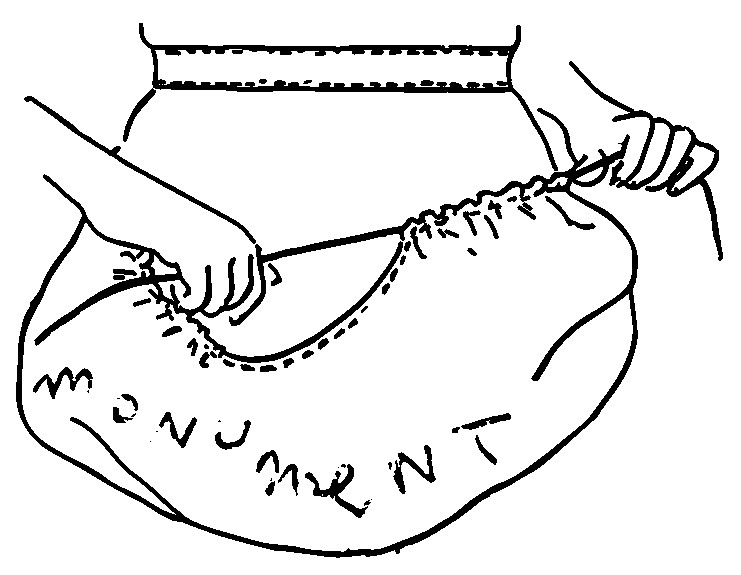

It was 1975, on a central street in downtown La Coruña, southern Spain, that ZARA was born. Ortega, the son of a railroad worker, had planned to call his first shop Zorba after his favorite film character, but coincidentally found a neighboring bar with that name, thus thwarting the attempted association to the hedonistic tendencies of a man larger than life. Having already taken the pains to lay molds for the shop’s sign, Ortega got down on his knees and began rearranging the letters by hand. In this way ZARA gained a decidedly more feminine but perhaps no less commanding character.

If you’re wondering where the additional “A” came from, there is speculation that there had been another set of letters. It is also noted that at the time the price for the letters “B” and “O” were significantly higher due to the additional labors of making a rounded edge. At any rate, this is only a minor detail of our story.

The first ZARA products resembled high-end fashion brands and, naturally, instantly became wildly popular. Struck by his success, Ortega began opening more and more stores like an obsession. His compulsion to make newer, trendier garments faster, led him to revise the design, manufacturing and distribution strategies, reducing lead times and enabling the company to respond to market wants quicker than ever before. “Madness,” he could often be heard saying to himself, “a man just needs a bit of madness.”

For all its speed, ZARA became known as a “fashion imitator” (a reputation it still holds today) producing low-priced goods faster, rather than dwelling on stylistic innovation. But its executives would (and still do) vehemently refute its characterization as derivative of runway trends. It’s governance, they claim, relies solely on the strength of desire. ZARA only responds to what its shoppers want, they chirp. And it’s true that today you can visit any ZARA store and you’ll find the precise strapless sandals of your dreams, before you’ve even dreamt of them.

2

But how exactly did this rapid ascension take place? What has fueled such merciless drive? Industry insiders are in constant awe of ZARA’s ability to turn products around in a mere week compared to the six-month average. Its 12,000 new designs per year overshadow the meager two to four thousand standard of its competitors—H&M, COS, Mango, among them. “Instant fashion” Ortega is said to enjoy calling his creations, connoting a prepackaged food that springs to life once you pop it in the microwave.

Who is ZARA, and what makes her so inimitable? The director of Louis Vuitton, Daniel Piette, once described her as “possibly the most innovative and devastating retailer in the world,” with a palpable tone of both fear and reverie. There are different versions of this story and it is with good reason that the narrative remains meandering and elusive. This is not an analysis of retail psychology or branding tactics. Rather, the tale of ZARA is deeply human but rarely told. And this is because the interlocutors are dispersed, hidden, and confined to largely invisible spaces. Often, too, they are restricted to silence. There are those who imagine the global supply chain as a seamless space, composed of mechanized routes devoid of human touch. Some would like to think of it as an entity whose movements simply follow nature’s course, an animalistic logic of move or die. Still others would prefer to believe that it doesn’t exist at all. But you, dear listener, should know that these pathways circulate more than lifeless goods. Point your nose in the direction of the sea: In our case, ZARA is a watery being and her story is necessarily being kept at bay.

Consider that those fearful dark shapes that loom just beneath the water’s surface tell nothing of their actual matter and shape. Then hear that ocean liners crossing the Pacific transporting garments from factories in the South, also bear other, more precious cargo. In the hold are cramped living quarters where women and sometimes children wait attentively for the next wired signal. Storerooms are filled to the brim with bolts of blended fabrics—cotton, elastane, polyester, spandex, stretch denim—and tens of thousands of buttons, zippers and other trims. These are for making tank tops, jeans, T-shirts and underwear, sometimes socks. If you listen closely, a soft chanting can be heard emanating from within the ship’s deepest chambers: “Diro, Kalvin Clein, Muccci!” drones a polyphonic chorus. In between this perturbed couture legacy, other lyrics are whispered: “feelings dance only by putting it on…”

This is a ballad of minor ecology. Those songs that seep from the hold are not the cries for pity or help, but gasps and murmurs of a perverse autonomy. Along these fluid lines strange synapses and assemblages have grown, new subjects are forming. I know this because I am one of them—or at least one head of this many-headed hydra, the hydrofemme: we are water and so are you.

3

Where fast fashion races beyond the borders of labour law, chasing an endless sun westwards so the timecards never clock out, our hydrofemme’s seafaring domesticity is countered by a mutinous perruqué: among the piles of perfectly cut skinny jeans and deliberately “distressed” shorts are what are known as “seconds”—the excess and the not-to-quality-control-standard. These pieces, ranging from perhaps a tiny sewing mistake to even a whole extra sleeve, represent the myriad deformities swimming in the undercurrents of global production. They are what surpass management and control systems to form the lyric of hydrofemme’s subversion. We call it shuihuo, literally meaning “water goods” in her native language. The term stems from a real life network of goods that she has appropriated and, wrapped carefully in plastic, cast back into the sea. These shimmering buoys glisten under the moon like aberrant waves lapping on the water, and they are markers to those on shore who know to look for them. But where traditional markers serve to coordinate a striated geography, water goods escape control and taxation to rewrite the relations between makers and users. Indeed, these are one-of-a-kind pieces, without serial number and gently passed each and every one through the hands of ZARA the creature who has long succeeded her maker. Contrary to what you may think, these are not those inferior products sold on some black market. Each evening, her contacts inland row out to the agreed drop points at sea and retrieve them as messages, love letters and beacons to join the song of a queer perfection. The network moves hand-to-hand, complex and undercover. They are slippery, these water goods, and while the factory at sea heads north and west, they refract against a Neo-Imperial course through a poetic potency which can neither be tracked nor reclaimed.

At sea, time is mutable. It unfolds and multiplies depending on a discreet set of coordinates. Our ancestors, the pirates and corsairs, understood that the shifting topologies of these in-between spaces were only synthetic. And none of them better versed in this than one, a widow by the name of Ching, who once ruled the South China Seas. At her peak the Widow Ching, as she was known, commanded a fleet of 1800 ships, supporting some 70 to 80,000 pirates. She had gained her position when her husband, a merciless man who until his death at the hands of an adversary had terrorized the region. Staving off mutiny, Ching married the younger but promising Chang Pao to whom she delegated the task of commanding battles while she herself set about sorting the tidings of business. Establishing a legal code to protect and support her fleet, she also instated a fee permitting merchants to pay for safe passage through pirate waters. Among these regulations were those that dealt harsh penalty to those engaging in unequal gender relations. Women aboard the Widow’s ships had agency and expect, if not to thrive, then at least to have a pirate husband who, once consummated, would be a responsible and faithful partner in crime.

This ad-hoc governing scheme reined from 1776 to 1800, a time during which pirates and non-pirates could be found cohabiting. It is likely from this period that the term “ahoy” originates. Contrary to popular belief of its origin from the Netherlands (“hoi” in the modern Dutch language is still a common casual greeting), whispers from the South China Sea reveal a different etymology. Indeed, the Dutch East India’s exploits in Asia during the mid-1700s were already in decline due to increasing competition from other traders, such as the Austrian Netherlands founded Ostend Company operating direct trade between China and Europe. Thus while a triumphant “a hoi” in Dutch or German has been interpreted as a declaration of “Land in sicht!” (land ahead) to colonial callers, our story reveals this to be their misdirected echo of our southern pirates’ call. “啊海 (a hoi)” meaning “to sea!” in the native southern dialect was an ecstatic cry in the opposite direction, outwards from the shore. A direct counter to imperial expansion, 啊海 a hoi could be found resonating from ship to ship, as a call for collectivity and unity used by the members of Widow Ching’s fleet when under siege. The emphatic, waterward-orientation of such an expression suggests the sea as a safe, fertile space rife with potential—that is, if one knew how to harness it. The Widow Ching was undoubtedly versed in such malleability. After striking a deal with the British and the imperial Qing court in 1810, the Widow finally settled down, becoming one of the only pirates in history to ever retire from her post, founding a small but successful nightclub in Guangzhou.

4

ZARA doesn’t tell you what she wants because she doesn’t need to. Dear listener, she never asks for anything. On the ground, her trend forecasters are out in throngs waiting to tap into what’s “à la mode”. A wire signal sent out to sea sets dozens of sewing machines whirring. By the time the ship reaches shore, several hundred thousand pieces have been sewn and the instant you feel a compulsive urge to buy a particular version of cropped tee, it has already miraculously appeared on the shelves—at a store near you.

At this point, your confusion concerning the skeptical nature of our heroine is warranted. The hydrofemme is a becoming mythology, and her implications within the mainstreaming of desire are meant to be read like the passing of the thousand philosophies adorning t-shirts in public space. The representations contradict or even satirise their wearers, and while she may be superficial, her impact is anchored much more deeply than those donned layers of ready-to-wear. Indeed, it is because she is always ready-to-wear that she slips through identity so fluidly and mercilessly, and her materialisms turn over, transmit and replicate.

Desire is a funny thing. Before a single stitch is sown, before the thread hits the needle’s eye, it’s already born. Fashion is fast, but the ocean is oh so slow. Between its waves you can catch glimpses of the many eyes of the hydrofemme that is ZARA—the fetish, and the factish god. We are part of this refracted gaze. You may not always see us directly, but we are there—in the “sequins of sequence” lining your décolletage, glinting from the pearl button on your sleeve, and swaying lightly in the hem of your skirt. We seized the means of production and channeled distribution to places it never should have gone.

ZARA, among other things, is a war machine that traverses the seas silently and relentlessly. Because her movements are often more dictated by economic currencies than watery ones, they are not always straightforward. This makes her a difficult beast to catch.

評價 Reviews

Your e-mail address will not be published

* 必填 Required fields